The neighbourhood of the IMP and the wider Vienna BioCenter may seem very modern, but beneath the surface lie the remnants of a rich and multifaceted past.

Settlements in the area go back at least 4000 years, documented by Neolithic artifacts. Remains of Bronze Age tools and Iron Age burial grounds have been found close to where the IMP is located today. Evidence of the La Tène culture, established by Celtic tribes in the fifth century BC, comes from a variety of coins found along today’s Rennweg road. Around the year nine B.C.E., the Celtic Kingdom Pannonia was incorporated into the Roman Empire, and developments in the area are picking up, gradually shaping the neighbourhood's present face.

Busy Roman life

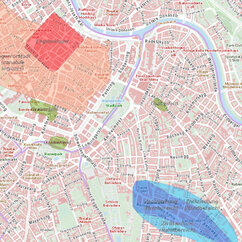

2000 years ago, the Danube marked the northern border of the Roman empire. Among the fortifications along the river was the legionary camp of Vindobona, located at the heart of today’s capital city. A busy highway tracing contemporary Rennweg connected the fortress to Carnuntum, the regional administrative centre of Pannonia. Both camps were situated strategically along the Limes frontier. Another main road ran along today’s Landstraßer Hauptstraße and joined on to the Limes road at the south-eastern corner of the Vienna BioCenter. From the first century AD, there is evidence of a civilian settlement - a municipium - on what is today’s third district. It was home to the romanised local population - craftsmen, tradesmen, and artisans - but also to veterans and their families. A wealth of artifacts from this time bear witness to a rich and busy lifestyle.

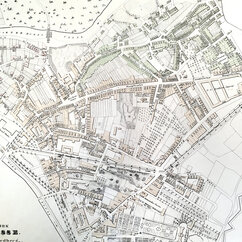

Gallery pre-1840: from Roman rule to hospital & care facility

Rescue excavations carried out in 2010/11 along Rennweg 94-102 unearthed the foundations of a Roman residential building, a number of workshops, rubbish dumps filled to the brim with pottery shards, a child’s grave and the surface of a road that might have connected the limes road to the main highway to Aquae (Baden) and Scarbantia (Sopron).

From medieval wasteland to Baroque travel hub

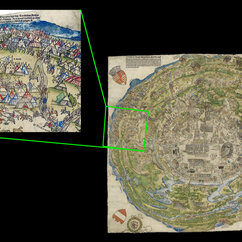

After Vindobona had lost its significance for the defence of the Roman empire, only a small number of settlers remained. During the Early Middle Ages, the area of St. Marx seems to have been uninhabited for several hundred years, as indicated by a thick layer of topsoil covering the Roman ruins. It was only in the Late Middle Ages that Vienna was developed into a thriving town under Babenberg rule, protected by fortifications and endowed with municipal privileges. Today’s Rennweg was still one of the main routes leading east and was frequented by travellers and tradespeople.

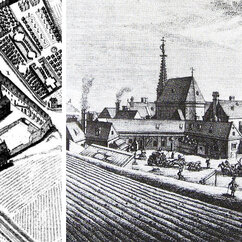

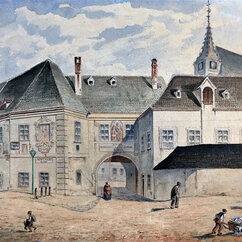

Fearing the spread of infectious diseases carried by returning pilgrims, the Order of Saint Lazarus chose this site - a fair distance from town - to establish an infirmary in the early 13th century. An associated chapel was known as “Saint Mark’s” and later lent its name to the entire neighbourhood. The infirmary was soon converted to a civic hospital, tending mainly to the poor. Leprosy was widespread and several outbreaks of the plague decimated the population by almost two thirds.

In 1529 and 1683, Turkish troops besieged Vienna – events deeply rooted in the memory of the city. The attacks were unsuccessful both times but caused considerable damage to the suburb of St. Marx and to the hospital. By 1706, the rebuilt hospital was moved under the administration of the Bürgerspital, used especially for syphilitic patients, people with epilepsy, "fools", and unmarried pregnant women. St. Marx's brewery (see below) and bakery provided beer and bread for itself and the main Bürgerspital.

In the neighourhood of St. Marx, a second and wider ring of walls was constructed to incorporate and protect the suburbs. Remains of this “Linienwall” that later on served as a tax border are still visible around the Vienna Biocenter.

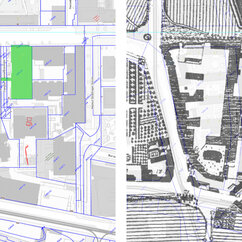

Gallery: Linienwall - outer city walls

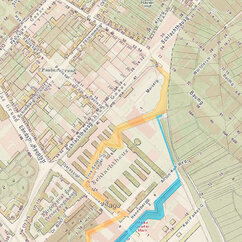

A forgotten waterway

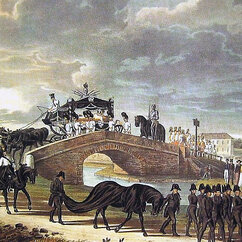

Growing in population and strategic importance, Vienna became a busy travel hub and by the late 18th century, 40,000 horses a day transported people and goods between Vienna and the port of Trieste. An ambitious project to connect the capital to all European oceans was dropped for lack of money, but around 1800 a narrow canal, originating in St. Marx, was constructed to ship goods to Vienna from the South (“Wiener Neustädter Kanal”). The waterway, which was originally supposed to reach the Mediterranean, never made it past Wiener Neustadt, some 60 km south of Vienna. It was mainly used to ship coal at low costs but was rendered unprofitable by the advent of the railway.

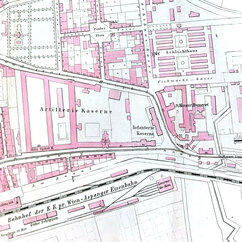

The canal was eventually filled up and the site of the harbour-basin was chosen for the terminal station of the “Aspangbahn” railroad-line, opened in 1881. Today, the train station is replaced by residential developments and mainly remembered for its tragic role in the Holocaust. Between 1939 and 1942, over 47,000 Jewish men and women were deported to concentration and termination camps from here, including at least two biologists, the zoologist Leonore Brecher and the botanist Helene Jacobi. As a reminder to the deportations, a memorial was opened at Leon-Zelman-Park in 2017.

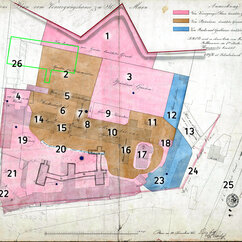

Gallery 1840 to 1913: St. Marx industrialises

A long brewing tradition: from hospital to brewery

The hospital of St. Marx had been brougth under administration of the Bürgerspital in 1706. Further reforms brought about by Emperor Josef II during the age of enlightenment included the construction of Vienna’s General Hospital to which the patients of the St. Marx hospital were transferred in 1784. St. Marx then served as a care home for poor and elderly (Versorgungshaus) until 1861.

Since the 14th century, the providers of St. Marx had been allowed to produce and sell beer on the grounds, a privilege granted to top up the meagre budget of the asylum. After the 1706 merger with the Bürgerspital, the hospital maintained the brewery, but started renting the brewing privilege to frequently changing independent brewers in 1733.

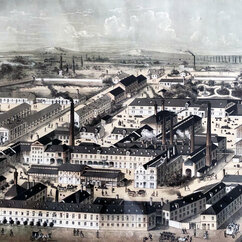

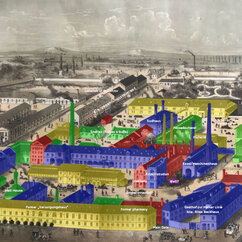

In 1840, the Bohemian brewer and entrepreneur Adolf Ignaz Mautner leased the brewery and quickly expanded the business. Mautner was said to be very loyal to the emperor, having dispersed revolutionaries near the Linienwall with his staff in 1848.

Mautner was also very innovative, introducing bottom-fermented beer in 1843. In 1857, he purchased the entire premises of the Versorgungsanstalt (including the privileges to brew, bake, and sell beer) to convert them entirely into a brewery - leading also to the demolition of the St. Marx chapel, among other construction and refurbishments.

By 1861, the last residents of the care home left. Continuous reconstruction works and the introduction of modern technology and equipment quickly turned his company into Europe’s third largest brewery and Vienna’s most popular with a local market share of 75 percent.

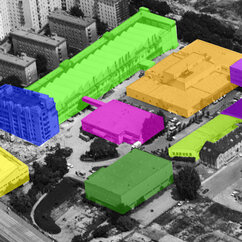

Remarkably, the approximately 1000 employees enjoyed a number of social benefits, including medical care, affordable housing, baths, canteens, laundries and a bonus system, all of which created a strong sense of loyalty. The premises covered a huge area, almost exactly overlapping with the grounds of today’s Vienna BioCenter and some neighbouring areas, and probably still leaving foundations and cellars in underground locations.

Production was thriving, turning out over 50 million litres of lager per year. Brewing came to a sharp halt in 1916, following a 1913 merger with the Anton Drehers Brauereien AG with its main brewery in nearby Schwechat. The St. Marx buildings were used as living quarters for a while but suffered substantial damage during WW2 and were eventually torn down in the early 1950s.

Gallery: between the wars

Post-War: new life on the old grounds

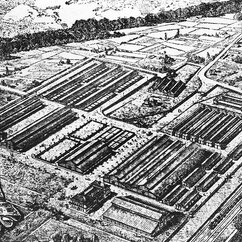

The grounds of the former brewery were partly turned into a residential area in 1953, offering subsidised municipal housing. The complex is named after Joseph Madersperger, the inventor of the sewing machine, who spent his last months in the care home and was buried at St. Marx. Along the newly constructed Dr. Bohr-Gasse (named after the physician Oskar Bohr), the company Philips built a factory to produce consumer electronics. From 1955, the popular radios featuring the new transistor technology were manufactured here and marketed under the brand name of Hornyphon – an Austrian company that Philips had taken over in 1936.

Portable radios became all the hype, and a new production hall was added in 1960. Towards the end of the decade, the focus of the production shifted to television sets and in 1978 was replaced by video equipment. After a new video-plant in the South of Vienna had gone into operation, the factory in St. Marx was no longer in use and in 1984 became the property of the WWTF (today’s Vienna Business Agency).

Gallery: radio and TV factory of 1950s to 1980s

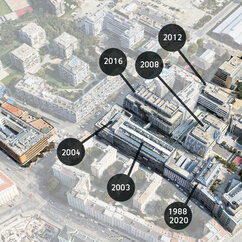

Still in good shape, the administrative main building of Hornyphon underwent a complete makeover and in 1988 became home to the IMP. The parts of the factory where the new (2016) IMP building is located were used as a print facility by the publishing company "Vorwärts" from 1986, called Büro- und Druckereizentrum Viehmarktgasse. The patronage of St. Marx did not prevent the Socialist publisher from going bankrupt only two years later.

The site of where the current IMP-buidling would be constructed until 2016 was bought up by Mediaprint in 1988. Several print- and publishing outlets operated here until 1992, while the cusping IMP was in its first building nextdoor. Products ranged from newspapers (including the first edition of Austria's daily paper "Der Standard" in October 1988 and the tabloid Kronen Zeitung) to labels and tickets. In 1992, Vienna's hospital administration KAV moved in and used the buidling for its centralised IT services.

Gallery: St. Marx goes Life Sciences

Near the Vienna BioCenter

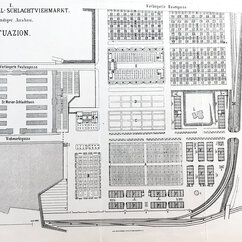

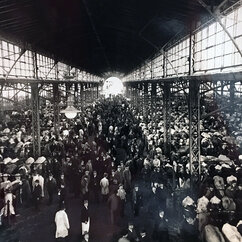

In 1850, St. Marx and its neighbouring suburbs were incorporated into the City of Vienna. Within the following seven years the population doubled, mainly due to the influx of workers from Bohemia and Moravia seeking employment in one of the rapidly developing industries. Growing demand and increased hygiene standards led to the construction of Vienna’s largest abattoir with an associated livestock market. St. Marx was chosen for its convenient location in the East since the majority of the animals were brought in live from Hungary. Enlarged and modernised multiple times, the slaughterhouse partly remained in operation until the 1990s. Today, a number of the buildings remain, impressive by their sheer size and elegant-functional brick architecture. Protected as historic monuments, they now serve as stylish homes to the creative and catering business. Visitors approaching the IMP are to this day greeted by two enormous bulls (representing the Austrian and the Hungarian parts of the long-gone Empire), towering over the historic entrance gate.

A ten-minute walk separates the IMP from a well-hidden cultural and natural treasure, the former cemetery of St. Marx. Following a sanitary directive by Josef II, it was created in 1784 on grounds outside the city walls to replace several smaller, more centrally located graveyards. In operation for less than 100 years, the St. Marx cemetery is now a historic park that attracts visitors not only for the remains of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart but also for its charming mix of quaint Biedermeier tombstones, lush vegetation, rich bird life and a colony of wild hamsters.

Vienna's urban sprawl stretches across several levels of altitude, created by alluvial deposits during the successive ice ages. The area of St. Marx sits on one of these terraces, the terrain sloping down towards the Donaukanal. However, walking in a north-eastern direction from the IMP, one encounters a surprisingly steep drop in elevation. This used to be the undercut riverbank of the ancient Danube, a so-called "Prallhang". Today, it is labelled as a natural monument and associated with a small patch of urban wilderness on its top. Underneath the little refuge for stray cats and well hidden from curious explorers lies an extensive system of underground vaults that were used as ice-cellars by the brewery. In recent days, the space has been used by a commercial mushroom grower and as shooting range by a sports club. Apart from these mundane purposes, there are lots of rumours surrounding its role during the second world war, from secret production site to strategic hiding place.

For centuries, silk - though rare and expensive - was in high demand as fabric for garments and imported in substantial quantities, mainly from Italy. Starting in the 17th century and in line with the ideas of mercantilism, landowners were encouraged to grow mulberry trees as food for silkworms in order to establish a silk processing-industry in Austria. The Turkish invasion in 1683 put a temporary end to these initiatives, but a century later, several plantations existed in and around Vienna. The nurseries that raised the trees were subsidised and saplings of white mulberry could be obtained for free by those willing to tend to them.

One of the larger nurseries was located at today’s Ungargasse and a mulberry-plantation plus silk-factory existed at Rennweg, not far from the orphanage. The neighborhood thus offered a supply of young girls who could be trained by Italian specialists to unwind the delicate threads of silk from the worms’ cocoons. Although a lot of effort was put into the initiatives, many trees failed to survive and the silk that was produced in Vienna was of mediocre quality. The outbreak of a silkworm-disease in the mid 19th century finally put an end to the experiment, with street-names like Seidengasse (silk-road) being all that is left.

In the late 17th century, Vienna felt increasingly threatened by Hungarian anti-Habsburg rebels, the Kuruc. To protect the city and its suburbs from the invaders, a second and much larger ring of fortifications was to be built. Construction of the so-called Linienwall started in March of 1704 and was completed just four months later. To finance the project, a special tax was imposed and citizens between the ages of 18 and 60 also had to labour in the construction.

The 3.8 metre high and 4-metre-deep rampart was initially made of soil with palisades, and further fortified with bricks in 1738. Built in a zigzag-line and surrounded by a three-metre-wide ditch on the outside, it partly followed the outlines of the developed area and also took advantage of a natural border defined by Vienna’s terraced geography. The 13.5-kilometre wall started at a branch of the Danube in St. Marx that dried out in the early 18th century, requiring a minor adaptation of the Linienwall. A later and more substantial change in the course of the wall was owed to the construction of the slaughterhouse St. Marx in the mid 19th century.

Due to lack of money, maintenance of the wall was neglected, and security patrols were inadequate. The Linienwall was never in sufficient shape to provide adequate protection. But with the last of the Kuruc attacks happening in St. Marx in 1704, when 2600 Viennese citizens and 150 students repelled the attackers, it did not need to withstand any further invasions. When Napoleon’s troops conquered Vienna hundred years later, advanced artillery technology had rendered such fortifications futile.

Instead, the Linienwall was ideally suited to serve as a toll border. Its nine gates – including one just outside of today’s Max Perutz Labs at Rennweg - were located along major roads and could be controlled easily. During the 18th century, each of them was complemented by a small chapel and three administrative buildings where civil servants carried out their unpopular duty.

With life in Vienna becoming ever more expensive, the middle class preferred to settle in the inner suburbs (Vorstädte). In 1850, they were incorporated into the city and in 1890 the outer suburbs (Vororte) followed. The Linienwall, now obsolete, was demolished in 1893, paving the way for a number of major building projects: the Gürtel road that circles the inner districts, the Stadtbahn railway which has been replaced by U6 and the regulation of the river Wien which ended the constant threat of flooding. Only very few parts of the original wall remain to this day. Two of them are located close to the Vienna BioCenter, just off Anton Kuh Weg. A smaller part dates from the 18th century and has been incorporated into the emergency exit of a school building. The longer part is a remainder of the 19th century reconstruction.

More substantial remains are still buried underground and are occasionally excavated during construction works. A 30-metre-long section of the wall was uncovered next to the IMP in 2006, when the grounds were prepared for the Valneva (former Intercell) building. The same emergency excavation also produced the bones of around 150 humans that had been deposited rather than buried in mass graves associated with the former hospital.

Further Reading

History of Hospital St. Marx (German)

Impressions of St. Marx Brewery

"Wiener Bier-Geschichte", illustrated history of beer in Vienna by Christian M. Springer, Alfred Pleczny, and Wolfgang Ladenbauer. Böhlau Verlag Wien, 1st edition 2017, 2016 (German).