A Home for Curiosity and Knowledge: How the IMP resurrected a radio factory

For almost thirty years, the IMP was housed in a former industrial building that had been ingeniously adapted to accommodate researchers and their equipment. Undergoing numerous small adaptations, the building served its purpose with restrained elegance and unfailing versatility. After its second metamorphosis, it now offers space for innovative ideas and young enterprises.

In October 1986, Max Birnstiel became director of the newly founded “Institut für Oncogenforschung” in Vienna. Within a few months, the first group leaders were recruited and their teams were working in the labs of the company Bender, now the Boehringer Ingelheim Regional Center Vienna. This temporary solution was soon to be replaced by a designated research building for the new institute. A property had already been set aside by the local authorities.

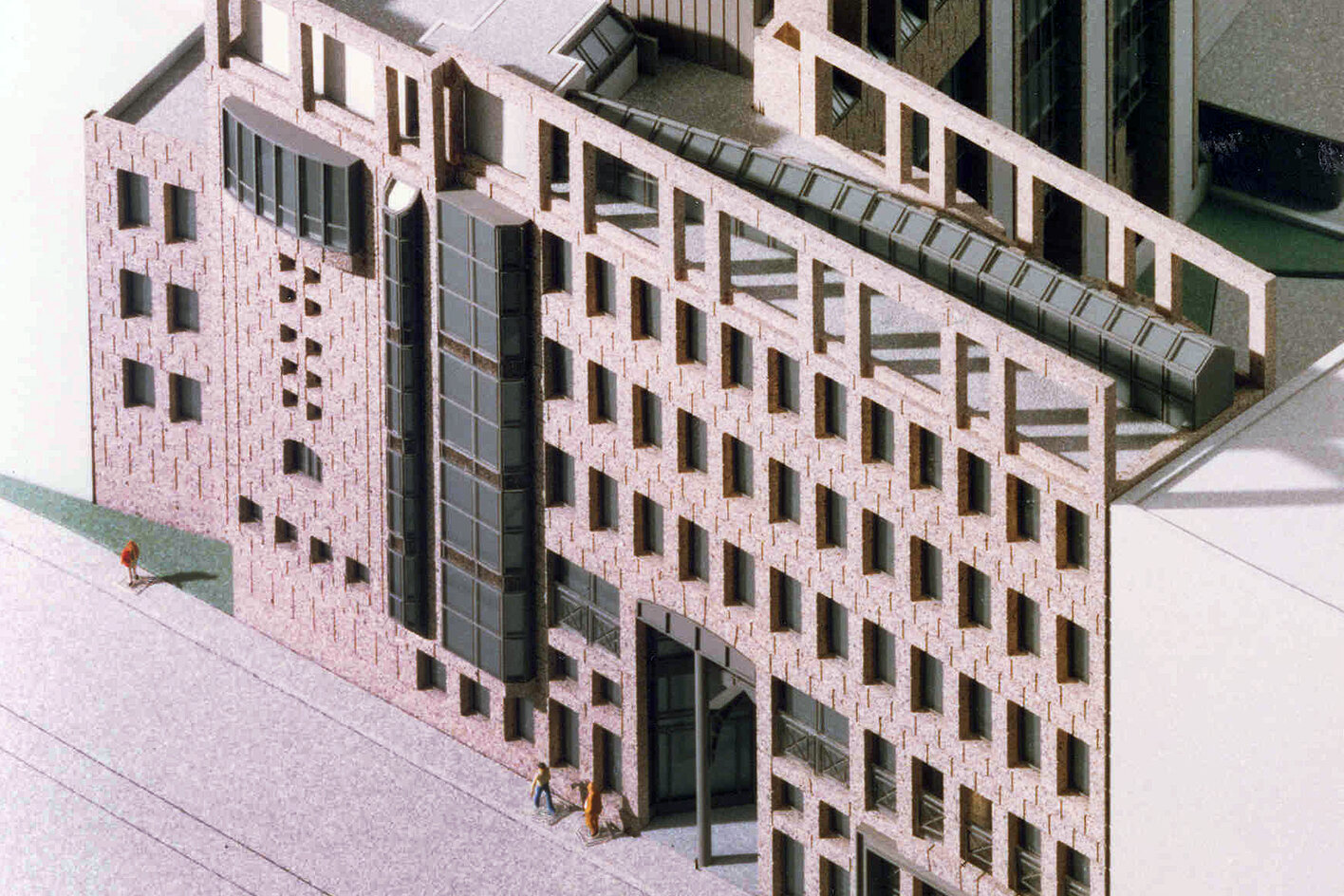

Situated on Dr.-Bohr-Gasse in Vienna’s third district were the remnants of a former radio factory. Built in the 1950s, it had been the production facility for transistor-radios and TV-sets sold under the brand-name of Hornyphon. When Philips, by then the owner of the brand, had moved to a larger site, the premises were acquired by the City of Vienna and later became the property of the WWFF – today’s Vienna Business Agency.

Although located in an unsightly neighbourhood, next to warehouses and the extensive grounds of the former abattoir, the property was conveniently accessible both from the center of town and Vienna’s international airport. With the slaughterhouse now redundant, there was also ample space for future developments. And there was an attractive financial incentive: the WWFF would rent out the premises for a token fee of one Austrian Schilling per year.

Keenly involved throughout: Max Birnstiel

Even before his contract was signed, Max Birnstiel was already deeply involved in the planning of ‘his’ institute. After Bender had carried out early feasibility studies, he invited Swiss architects Nik Streiff and Markus Haefeli to work on the project. Their conceptual design was convincing and by mid 1986 it was decided to remodel the old factory-building rather than to replace it. Vienna-based architect Peter Podsedensek was subsequently commissioned with the realisation and the actual reconstruction was done in just eleven months. By March 1988, the major works were completed and two months later the IMP’s opening was celebrated in a festive ceremony, followed by an inaugural scientific conference.

It was one of the prerequisites for the foundation of the IMP that it should not operate in isolation. Modelled after successful examples in the USA and the UK, close ties were to be established to university institutes, and some of them were to be relocated to the emerging research hub in St. Marx. The building plans took the future development into account and allowed for the shared use of the IMP’s library, lecture hall and cafeteria.

Max Birnstiel’s prior experience as head of an institute at the University of Zurich provided valuable input for the IMP’s design. His concept of how to create a stimulating research environment included details such as the choice of carpentry or the type of lab furniture and was also reflected in the general layout. The decision to favour a central cafeteria over several small tea-kitchens is just one example and it turned out to be priceless in encouraging communication and collaboration within the IMP and beyond.

30 years of innovation

However, converting an old radio-factory into a modern research institute posed some serious challenges and restrictions. Since the room-height was a given, there was not enough space to accommodate the necessary plumbing and wiring under the ceiling. As a solution, the architects devised a kind of exoskeleton and fed the technical supplies beneath the newly mounted façade. Born out of necessity, this approach gave the IMP-building some of its distinct features.

For almost three decades, the IMP building catered to the ever-changing demands of researchers and technologies. In addition to numerous small modifications, it also underwent major reconstruction works. In 1992, the university-building next door was opened and a passageway was created, connecting the two buildings via the top floor – marking the birth of the ‘Vienna Biocenter’. Three years later, four of the adjacent shed-halls were incorporated into the IMP, providing space for the new Max Perutz Library, a generous workshop and much needed study-room. Construction on the newly founded ‘Life Sciences Center Vienna’ of the Austrian Academy of Sciences started in 2003 and by 2006, the IMP was physically and thematically connected to two newly founded institutes - IMBA and GMI. Simultaneously, the IMP cafeteria underwent major remodelling and was scaled up to cater to the rising number of customers.

Despite the building’s versatility, it became increasingly difficult to accommodate the advanced scientific equipment that researchers required. When the technical infrastructure finally reached its limits, the decision was made to construct a new research institute from scratch. From 2017 to 2020, the former IMP building underwent a major transformation and today offers co-working labs and office space, especially for start-up companies.

Key figures

Total reconstruction costs: 235 Mio ATS (ca. 17 Mio EUR)

Reconstruction time: 11 Months

Lot size: 1,019 m2

Gross floor space (before 1995): 7,500 m2

Net area (before 1995): 4,119 m2

Floor height: 2.8 m

Support grid: 7.2 m

Number of floors: 8 (2 underground)

Material: Reinforced concrete, brickwork, natural stone (façade)