Seeing proteins fold as they are being made

As ribosomes build new proteins, folding begins while the protein emerges. By capturing a chaperone, a helper protein, bound to a ribosome, researchers from the lab of David Haselbach and collaborators reveal the entire picture of how chaperones guide this cotranslational protein folding in yeast.

Inside a living cell, there is little room to manoeuvre. The cell’s interior is densely packed with molecules, constantly moving about and bumping into one another. In this environment, making a new protein is not just about the ribosome linking amino acids into a chain: A loose, unfolded protein floating in the cell would quickly get tangled and stuck to other molecules. As soon as a protein begins to emerge from the ribosome, the growing chain must therefore already start folding into the right three-dimensional structure – a process known as cotranslational folding. At one end of the ribosome, the genetic code is still being read; at the other, the protein is already taking shape.

This folding happens with a little help from chaperones, proteins that attach directly to the ribosome and interact with the emerging polypeptide, guiding it towards the correct form. So far, researchers have known which chaperones associate with the ribosome. What has been less clear is how these helper proteins are arranged on the ribosome, how they attach, and how they work together while a protein is being folded. Most importantly, the structural picture has been missing: J-domain proteins, the largest family of chaperones, had not been seen on a ribosome that is actively translating. Without this structural information, the mechanics of cotranslational folding have remained hard to pin down.

Catching cotranslational folding in the act

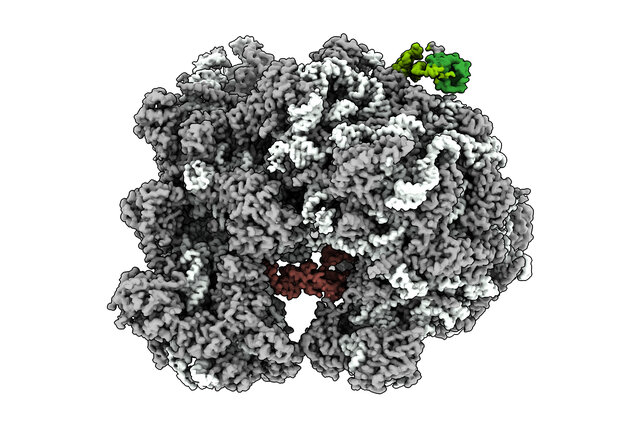

Writing in Nature Communications, the groups of David Haselbach at the IMP and Sabine Rospert at the University of Freiburg now capture a snapshot of folding in progress and clarify the entire process of cotranslational folding in yeast. By freezing translation at just the right moment – with an emerging polypeptide stuck in the ribosome – they were able to see how one J-domain chaperone specifically, the yeast Hsp70 family member Ssb, can bind both the ribosome and the growing protein and assists its folding.

Having solved the structure of the yeast Ssb protein, researchers now have a structural understanding of the entire cotranslational folding cycle in yeast. “We have filled a gap in the understanding of cotranslational folding”, says Haselbach. In other eukaryotes, the folding process is more complicated than in yeast and involves more chaperones. “Understanding the folding process in yeast is, however, a good starting point to understand how cotranslational folding works in other organisms.”

Solving a moving target

Making sense of cotranslational folding meant dealing with a basic contradiction: the process works because it is flexible, but that same flexibility makes it difficult to study. To overcome this, the researchers had to recreate folding as it happens, without freezing it into an artificial state.

Instead of working with isolated components, the team of Sabine Rospert rebuilt a translating system that closely mimics the situation inside the cell. Using actively translating ribosomes and engineering a polypeptide chain that stalls partway through synthesis, the yeast Hsp70 chaperone Ssb could bind in a native way. This produced a complex that was stable enough to analyse yet reflected the dynamics of cotranslational folding.

Even then, the system remained a moving target. When the emerging protein is folding as it appears, the chaperone moves with it—a nightmare for traditional structure determination. But this is precisely the kind of problem David Haselbach’s group specialises in. “The difficulty lies in the flexibility: The chaperone has to dynamically move and shape the emerging protein. But flexibility is our specialty,” says Haselbach.

Using cryo-electron microscopy, the team could resolve how Ssb sits on the ribosome, how it contacts both the ribosome and the nascent chain, and how it changes shape as it works. The structures reveal two major conformations—ATP-bound and ADP-bound—capturing the chaperone at different stages of its cycle and showing, in structural terms, how cotranslational folding is actively guided.

“The textbook view of folding, that a protein is first made and only then folded by chaperones, turned out far too simplistic,” says Haselbach. “We always assumed that the DNA sequence encodes the protein structure, which is only true to some extent: Once parts of the protein fold, they limit the structure the remaining protein can adopt. Cotranslational folding shapes a protein’s final structure from the very beginning.”

Original publication

Ying Zhang, Lorenz Grundmann, Leonie Vollmar, Julia Schimpf, Volker Hübscher, Mohd Areeb, Irina Grishkovskaya, Anna Moddemann, Kerstin Werner, Thorsten Hugel, David Haselbach and Sabine Rospert (2025): „The cotranslational cycle of the ribosomebound Hsp70 homolog Ssb“. Nature Communications (2026). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67685-6.