How Genetic Grammar Shapes Antibody Evolution

Our B-cells use somatic hypermutation to fine-tune their DNA code to make better antibodies — but not all DNA sites are treated equally. A new study from the Pavri lab at the IMP shows that somatic hypermutation depends not only on specific DNA motifs targeted for mutation but also on their surrounding sequence and their position within the antibody genes. This “genetic grammar” governs how antibodies evolve to improve immune recognition.

Most cells in our body work hard to preserve their DNA – the instruction manual for making all necessary proteins – by quickly correcting any genetic mutations that might alter these instructions and result in faulty proteins. However, a special type of cell does the exact opposite – it deliberately mutates its own DNA.

B-cells, the immune cells responsible for producing antibodies, intentionally introduce mutations into a specific region of their DNA – the variable region – which encodes the tips of their antibodies. This process, known as somatic hypermutation, generates slightly different antibody versions, which are then tested and selected so that only the best performers remain. This targeted mutation and selection process is essential for fine-tuning our adaptive immune response, helping the body recognise and eliminate pathogens more effectively during future infections and build long-term immunity following vaccination.

But somatic hypermutation isn’t random. It’s driven by an enzyme called activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID), which recognizes and mutates only certain “words” within the instructions sequence of the variable region, called WRCH motifs. However, some WRCH motifs are mutated more often than others, even when their sequences look similar. For years, scientists have theorized that the DNA sequence surrounding a WRCH motif – not just the motif itself – can affect how often it’s mutated, much like how the meaning of a word can depend on its context within a sentence. This kind of “genetic grammar” has remained poorly understood.

Now, a study led by Bianca Bartl and Ursula Schöberl in the lab of Rushad Pavri at the IMP, along with collaborators at the AC Camargo Cancer Center in São Paulo (Brazil), King’s College London (UK) and the National Centre for Biological Sciences, Bengaluru (India), sheds new light on how genetic grammar influences somatic hypermutation in B-cells. Their findings were published in the EMBO Journal.

The researchers studied whether the sequences around WRCH motifs influence how often they’re mutated. By swapping WRCH motifs into different sequence contexts, they found that each motif has its unique “genetic grammar”: placing one motif in another’s spot doesn’t guarantee the same level of mutation. The team also discovered that a motif’s position within the larger variable region also influences how often it gets mutated.

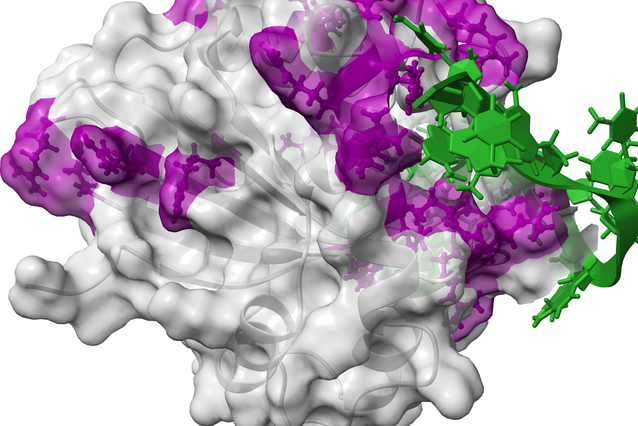

To explore how WRCH motifs and their contexts affect the strength of AID binding to its DNA substrate, the team performed molecular dynamics simulations, a computational method that uses Newtonian physics-based principles to “watch” molecules flex, bend, and interact in ways impossible to observe directly in the lab. These simulations revealed that both the WRCH motif and its surrounding DNA sequence affect, in distinct ways, how tightly AID binds to DNA.

These results suggest that the genetic grammar driving somatic hypermutation is governed by a complex interplay of sequence, context, and position. The study deepens our understanding of the molecular rules guiding antibody diversification with potential implications for antibody engineering and vaccine design.

Publication

Bartl, B., Schoeberl, U.E., Valieris, R. et al. Somatic hypermutation patterns are shaped by both motif position and sequence grammar. EMBO J (2025). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44318-025-00640-9