A cellular strategy for building protein-making machines

To keep cells running, ribosomes—the molecular machines that make proteins—must be built continuously and with high precision. Now, researchers from the lab of David Haselbach at the IMP, together with collaborators, capture ribosomes at their earliest stages of assembly and discover a flexible, modular strategy behind their construction. Published in Nucleic Acids Research, the study shows that ribosome assembly proceeds in parallel rather than along a strict assembly line, offering new insight into how cells reliably build their protein-making machines.

Ribosomes are the cell’s protein factories, translating genetic instructions into the molecules that keep cells alive and running. As these factories work nonstop, cells must constantly produce new ribosomes to keep up with demand. Keeping enough ribosomes in supply is one of the most energy-intensive tasks a cell performs, and it requires building them with precision.

In eukaryotic cells, ribosomes are assembled from long RNA molecules and dozens of proteins, with the help of hundreds of additional factors that guide the process. All these components must find each other and fit together correctly while the ribosomal RNA is still being produced, inside the crowded environment of the cell nucleus. If this finely balanced process goes wrong, protein production can be altered, affecting how cells function and potentially contributing to disease.

Scientists still do not fully understand how a ribosome comes together inside the cell—or what rules guide this complex assembly process. One reason is that the earliest stages of ribosome assembly are extremely difficult to study. The process unfolds very quickly, early assembly intermediates exist only briefly, many components are loosely attached, and some RNA segments appear only temporarily before being removed and discarded. Capturing these fleeting states and determining their structure has therefore been one of the biggest hurdles in understanding how ribosomes are built.

For a long time, ribosome assembly was thought to follow a simple, linear path: as the ribosomal RNA is produced, its parts would fold one after another, with proteins joining in the same sequence—much like steps on an assembly line.

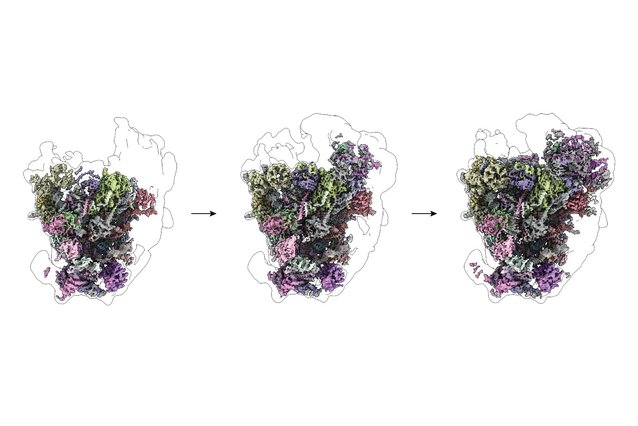

Researchers from the lab of David Haselbach at the IMP, together with collaborators, have now revealed how the ribosome comes together at its very earliest stages, discovering a flexible assembly logic that challenges this traditional view. By combining high-resolution cryo-electron microscopy with quantitative mass spectrometry, the team captured snapshots of ribosomes while they are still under construction—showing that different parts of the ribosomal RNA can form independently and in parallel, rather than in a strict, step-by-step order.

Robust by design: the modular assembly of ribosomes

To catch a ribosome in the act of being built, the researchers focused on a short RNA segment called ITS2. During assembly of the ribosome’s larger half—known as the large ribosomal subunit—this segment folds into a temporary structure called the “foot,” which serves as an early organisational scaffold before being cut out and discarded. By removing a key component of this scaffold, the team was able to slow ribosome assembly at an early stage, effectively pausing the process mid-build.

“That gives us a window into a phase we normally can’t see,” says David Haselbach. “Ribosome assembly usually runs so smoothly and quickly that these early intermediates are gone before you can catch them. Here, we could watch the ribosome while it is still coming together.”

To capture these fleeting moments, the team used cryo-electron microscopy to visualise the particles at near-atomic resolution, combined with a biochemical approach that showed which ribosomal proteins bind early and which join later during assembly.

The structures revealed that ribosome assembly is far less linear than previously thought. When the researchers interfered with the foot structure, one large region of the ribosomal RNA failed to fold—while another region assembled normally, even without it. This showed that different parts of the ribosome do not depend on each other in a strict sequence, but can form independently.

“It’s not like an assembly line where step two can only happen after step one,” says Haselbach. “Instead, different parts of the ribosome can come together in parallel, and the order doesn’t matter as much as we assumed.”

The same principle also holds for the ribosome’s smaller subunit, where the team captured several early assembly states following this flexible, non-linear logic. This modular approach makes ribosome assembly more robust, allowing cells to reliably build these essential machines even while their RNA components are still being produced.

These findings reshape the understanding of how ribosomes are built in eukaryotic cells. “We tend to imagine these processes as very orderly,” says David Haselbach. “But inside the cell, things are quite messy. What matters is not the exact order, but that the right pieces find each other. Ribosomes may just be one example of a more general strategy cells use to build complex molecular machines”

Original publication

Magdalena Gerhalter, Michael Prattes, Lorenz Emanuel Grundmann, Irina Grishkovskaya, Enrico F. Semeraro, Gertrude Zisser, Harald Kotisch, Juliane Merl-Pham, Stefanie M. Hauck, David Haselbach and Helmut Bergler (2026): “A comprehensive view on r-protein binding and rRNA domain structuring during early eukaryotic ribosome formation.” Nucleic Acids Research (2026). DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkag036