Illuminating the brain one neuron at a time

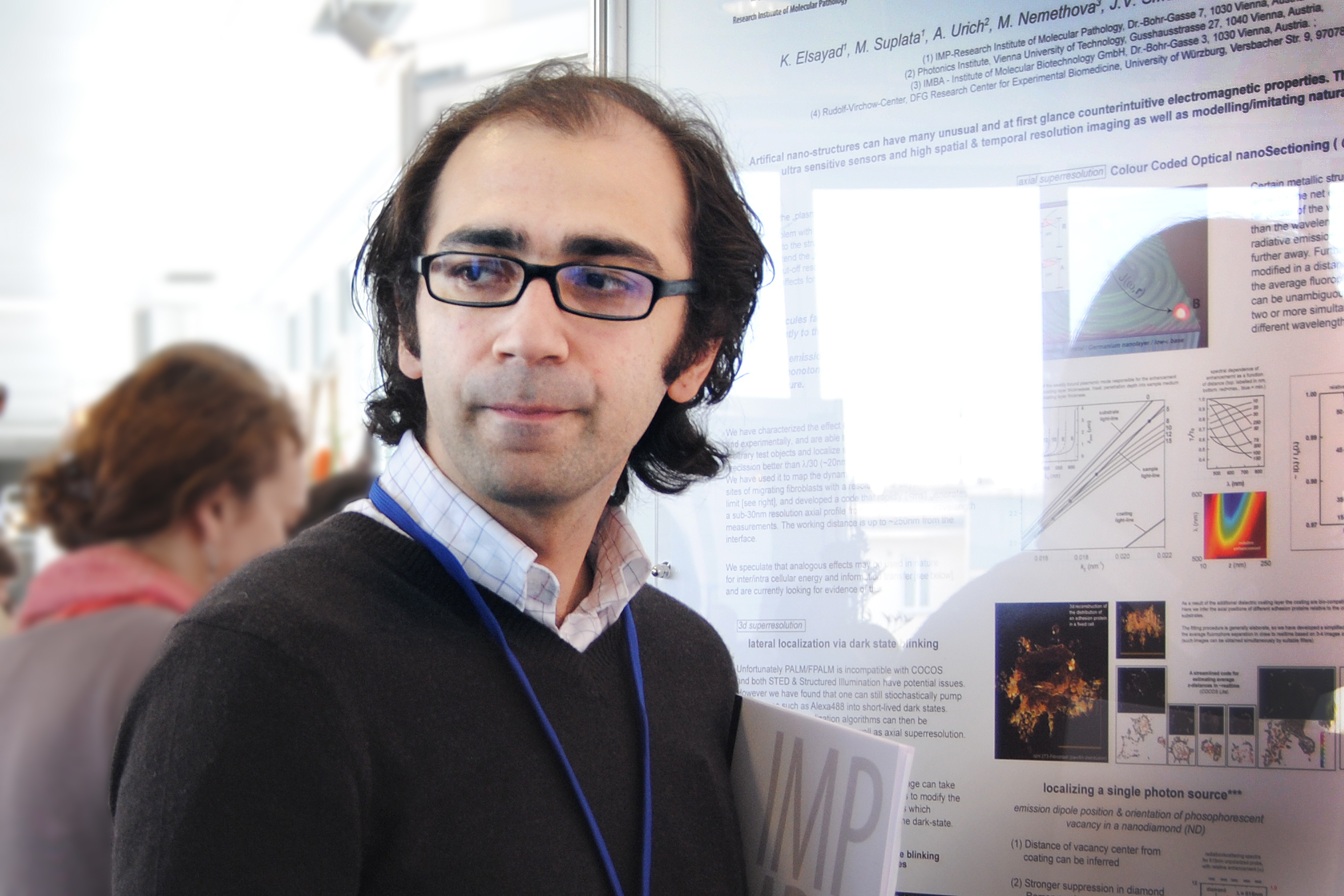

Alipasha Vaziri was a joint group leader at the IMP and MFPL (now Max Perutz Labs) from 2011 to 2016. His group successfully combined quantum physics and optical engineering with high-impact neuroscience, developing tools that can record activity from entire neural systems, and revealing fundamental insights into the limits of human vision.

Classical neuroscience focuses on individual neurons, using electrophysiology to record their activity and functional properties. Yet a wide range of brain functions and their underlying information are not encoded by individual neurons; they emerge from the distributed activity of highly interconnected neuronal networks. For example, if you randomly pick two neurons from the approximately 85 billion neurons in the human brain, the shortest signalling path between them comprises an average of just three or four connections. Thus, individual neurons might not carry relevant information, and to better understand how neurons generate behaviours, one needs to record the whole system while maintaining neuron-level resolution.

In the early 2010s, the most advanced imaging tools available were able to record activity from small neuronal networks by detecting the calcium influx that occurs when a neuron fires. At that time, recording the neuronal activity from the entire brain of a living organism seemed like a pipe dream. Indeed, when Alipasha Vaziri pitched the idea while looking for a PI position, many places dismissed it as unfeasible. But Alipasha had an unusual background for a neuroscientist—he had earned his master’s and PhD in quantum mechanics and optics under the supervision of 2022 Physics Nobel Laureate, Anton Zeilinger. What’s more, Alipasha was not afraid to embark on high-risk, high-gain projects—something that Robert Prevedel, the first member of the lab and currently a group leader at EMBL, can testify to. Luckily, the IMP and MFPL (now Max Perutz Labs) recognized Alipasha’s potential and recruited him as a joint group leader in 2011.

More than 100 neurons

Robert, who had a similar background to Alipasha, having also done his master’s and PhD with Anton Zeilinger, was intrigued by the idea of using his physics expertise to advance neuroscience. He set his sights on imaging the nervous system of C. elegans, a nematode worm whose entire complement of 302 neurons had been anatomically mapped with exceptional detail. “I was probably naïve because of my background—I wasn’t really aware of the challenges intrinsic to imaging biological systems”, Robert admits. But having an unprejudiced view clearly paid off—within half a year, the researchers had developed an optical technique called wide-field temporal focusing. Put simply, this technique allowed them to “sculpt” the distribution of light so they could overcome the traditional trade-offs between excitation area, resolution, and speed of recording.

However, this new method was only half the story. A collaboration with the group of Manuel Zimmer, also a PI at the IMP, was instrumental to the project’s success, as neurobiologists from Manuel’s team created a C. elegans line with a calcium sensor expressed solely in neuronal nuclei. Thus, neuronal activity only illuminated the nuclei, eliminating overlapping signals from axons and dendrites. Combining these physics and neurobiology innovations allowed the researchers to record the activity of approximately 70 percent of the neurons in the C. elegans head (Schrödel et al., Nat Methods 2013).

Up to 5,000 neurons

After this breakthrough, the Vaziri group was convinced that making microscopes faster and recording neuronal activity from larger volumes were both feasible and instrumental to advancing neuroscience. They then posed a fundamental question: what is, in principle, the fastest way to image neurons distributed across a large volume? This led them to work on light-field imaging, whose conceptual origins can be traced back to the early 1900s. Light-field imaging had found a revival in the mid-1990s and early 2000s, mainly in the context of photography, but had not been applied to functional biological imaging. Tweaking the method for neuroscience applications, the Vaziri group developed light-field deconvolution microscopy. By eliminating the need to scan multiple layers, this approach enabled the researchers to capture neuronal activity in volumes up to a thousand times larger at ten times the speed. In collaboration with a group at MIT, they used light-field deconvolution microscopy to image the activity of every neuron in C. elegans, as well as 5,000 zebrafish neurons (Prevedel et al., Nat Methods 2014).

Beyond transparent systems

These were remarkable breakthroughs, but they were helped by two very useful properties of worm and zebrafish brains: their small size and relative transparency. Would such tools be applicable to the opaque, highly light-scattering brains of mammals? The researchers went back to the temporal focusing approach of their first Nature Methods paper and—combined with a different signal detection technique—adapted it from a wide-field to a scanned configuration, suitable for deep imaging in scattering tissue. Scanned temporal focusing microscopy traded unnecessarily high spatial resolution (in conditions where the goal is to detect single neurons) for drastically improved speed, volume, and depth. This allowed the team to record calcium dynamics from up to 4,000 neurons distributed across different depths in the mouse cortex and approximately 2,000 neurons in the hippocampus of awake, behaving mice (Prevedel et al., Nat Methods 2016).

The human eye can detect single photons

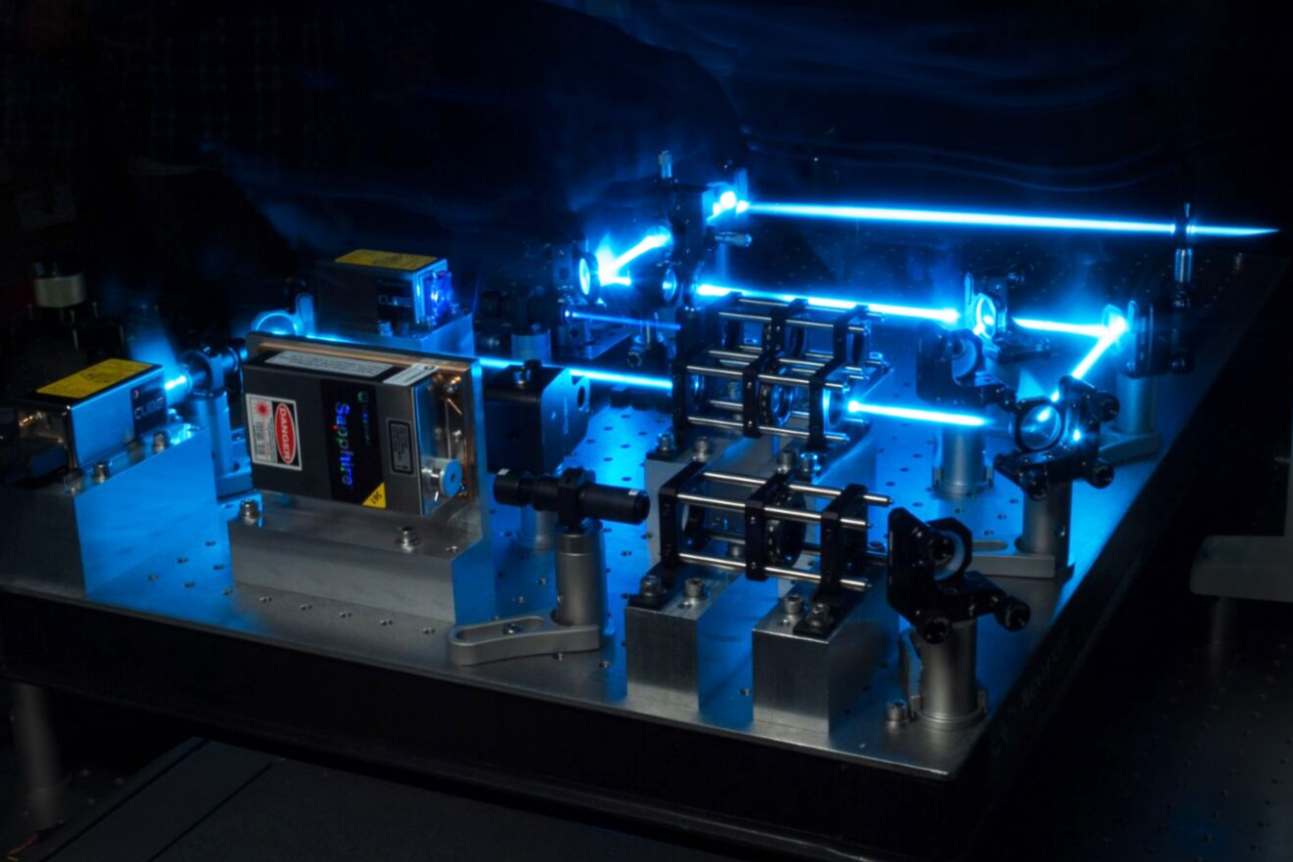

Beyond imaging technology, Alipasha and his team leveraged their expertise in quantum physics to ask a completely different question: what is the absolute limit of human vision? “Experiments dating back to the 1940s had shown that humans could detect weak flashes of light containing a few photons, but whether they could detect a single photon remained unknown”, Alipasha says. Answering this question was hampered by the inability to generate true single-photon states using classical light sources.

Using their expertise in quantum physics, Alipasha’s group created a quantum light source that generates pairs of quantum-entangled photons. While the generation of pairs itself is stochastic, energy conservation excludes unpaired photons. Thus, by detecting one photon, the researchers knew with 100 percent certainty that one other photon had been sent to the subject’s eye. Asking subjects to discriminate between a light stimulus and a blank, while indicating the degree of confidence in their responses, demonstrated that people can indeed detect single photons with a probability significantly above chance. By revealing sensitivity to individual photons, the study opened a path to explore whether the visual system responds to different quantum states of light, something Alipasha remains interested in.

A million neurons and beyond

“My time at the Vienna BioCenter was very formative—it laid the foundation for research that my lab is still continuing today”, says Alipasha, who moved to The Rockefeller University in 2016, becoming a professor in 2020. In the meantime, his group has developed tools for recording the activity of over a million neurons in the mouse brain. As predicted, the tools have revealed insights into how neurons coordinate to generate behaviour. For example, by performing whole-brain recordings in zebrafish engaged in a decision-making task, his team has been able to predict both the timepoint and outcome of animals’ decisions in individual trials up to 10 seconds in advance.

Finally, Alipasha’s work exemplifies how applying physics to biology enables new questions to be asked and answered. As Robert puts it: “For neurobiologists, these tools opened a new world”.

First published in 2026.

References

Brain-wide 3D imaging of neuronal activity in Caenorhabditis elegans with sculpted light.

Schrödel T, Prevedel R, Aumayr K, Zimmer M, Vaziri A; Nat Methods 2013

Simultaneous whole-animal 3D imaging of neuronal activity using light-field microscopy.

Prevedel R, Yoon YG, Hoffmann M, Pak N, Wetzstein G, Kato S, Schrödel T, Raskar R, Zimmer M, Boyden ES, Vaziri A; Nat Methods 2014

Fast volumetric calcium imaging across multiple cortical layers using sculpted light.

Prevedel R, Verhoef AJ, Pernía-Andrade AJ, Weisenburger S, Huang BS, Nöbauer T, Fernández A, Delcour JE, Golshani P, Baltuska A, Vaziri A; Nat Methods 2016

Direct detection of a single photon by humans.

Tinsley JN, Molodtsov MI, Prevedel R, Wartmann D, Espigulé-Pons J, Lauwers M, Vaziri A; Nat Commun 2016